- Countries Visited: 22 countries, all 50 US states, and Antarctica

- Travel Wishlist: Peru, Chile, Argentina, India, Jordan, my childhood home

- Locked down in: umm… Alaska, a brief trip through western Canada, then a drive across the upper left half of the US, and now Minnesota

“I’m still scared of getting sick, or my friends and family getting sick (so far at least 20 people I know have contracted covid, and a couple have died)”

I spent my 20th birthday sleeping on the deck of a tallship anchored in Key West harbor. That was the first night of a ten-day voyage that changed my life. Up until going to sea for the first time, I probably would have described myself as moderately risk-averse and somewhat of a homebody. I was (am) definitely a goody two-shoes, and I had basically always done what was expected of me: listened to my parents, gotten good grades, volunteered, gone to a prestigious college. But the first time we sailed over the horizon and could no longer see land in any direction, something in me shifted. In the middle of the ocean there are no well-trodden paths to follow, and so I started to understand that I could chart my own course.

When I was a kid, if you’d asked me what I planned to do after college, I would have answered “a PhD.” Instead, after my revelations at sea I finished my bachelor’s degree and then embarked on a wild ramble for the last 15 years that have led me to all fifty states, six continents, and a couple of oceans.

I’ve been molded into a friendlier, sillier, kinder, more open-minded, more flexible, person by the ridiculousness of helping my best friend prepare for a New Year’s eve drag pageant at the South Pole research station. Through the absolute annoyance of a cloud of midges in my face waking up on the banks of Loch Lomond with friends from college, and the solemnity of driving up to the coffined reactor at Chernobyl with a van of strangers. While giggling to stay warm in the cold and damp of the unheated B+B on a spring morning in Chefchaouen with my boyfriend, and through the lost-in-translation hilarity of trying to find rum in the middle of the night in Tegucigalpa and instead being directed to a gas station. While singing the American national anthem around a fire in Krueger National Park with the staff of tourist camp and screaming into my snorkel as a manta ray glided below me at the Great Barrier Reef with my parents. Through pushing a mini-van out of a ditch in Bavaria with my Girl Scout troop, and realizing that my friend’s bag hadn’t arrived in France for the beginning of walking the Camino de Santiago (or ever, as it turned out). And by feeling the bone deep peace of watching the first curl of smoke from a newly-lit campfire in Quetico Provincial Park with my campers. And, most importantly, people I’ve met along the way have shaped the course of my life. I became a nurse practitioner because of people I met while traveling.

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the immense amount of privilege that has allowed me to wander the world: financial privilege, racial privilege, the privilege of having an American passport, supportive parents, good health, a stellar education. I have been beyond fortunate in my life, and I know not everyone is granted even a fraction of what I have. I’ve tried to live up to that privilege in a variety of ways, including becoming a healthcare provider.

The beginning of the pandemic found me six months in to living in Anchorage, Alaska. After several years in primary care (and two “summers” spent working in adventure medicine at the South Pole research station in Antarctica), I had decided to get additional training in palliative and hospice care. I was lucky enough to be offered two fellowships, but I ended up choosing the one in Alaska over New York City because I’m not really a city person and because I didn’t know when I would have a chance to visit Alaska again (much less live there).

When I first moved to Anchorage, pre-pandemic, I got a two bedroom apartment because I was about to become everyone’s “friend in Alaska” and I anticipated lots of visitors. Friends from as far away as Australia and Vermont had planned trips to come to the frozen north. Most people had planned their trips for the warm months, but I had a few brave souls come visit in the winter. One of those friends arrived in early March, at the tail end of his own travels: 90 days backpacking through southeast Asia. We joked about covid (at the time it was making news, but hadn’t been understood as a real threat in most of the world) while we watched the ceremonial Iditarod start in a huge crowd of people, and while we ate Ethiopian food (in a restaurant, eating off the same platter, with our hands!).

He was the last visitor I was able to host. A week later, I woke up to a text message from my fellowship director: if I wanted to go back to the mainland US I probably needed to leave in the next few days. Covid had really and truly arrived.

So apparently a lot of Americans think Alaska is a island, because when they see it on US maps it’s always floating in a inset rather than being shown attached to Canada… On the one hand, that’s a little embarrassing and people should really pay attention to their history and geography classes in school. But on the other hand, in some ways they’re not too far off. While Alaska isn’t technically an island, it is remote. The only ways to get into Alaska are ferry (five days to Seattle), plane (3.5 hours to Seattle), and a highway through Canada that winds through the Yukon Territory and British Colombia (2,000+ miles to Seattle). And with the pandemic closing in, it was clear that some or all of those routes out would soon close.

I talked it out with my parents, thousands of miles away in Atlanta, Georgia, and decided to stay. While I acutely felt the distance from my friends and family, I had all of my nursing licenses in Alaska. I was scared, but I wanted to stay and help. I was literally in a fellowship to learn to help people at the end of their lives, and it seemed likely the pandemic was going to cause a steep uptick in people dying. Within a few weeks the Canadian border had been shut, the ferries had stopped running, and flights had been slashed. I had made my decision, and the early months of the pandemic were spent in Anchorage.

While Alaska didn’t impose a full lockdown, the governor and chief medical officer made some pretty smart choices that kept the initial surge low. But like many healthcare providers, I had concerns about how the virus was being transmitted, about whether I had the correct PPE, about whether I was going to get sick. Our hospital did a good job of protecting us, but that’s the kind of thing you can only know in retrospect. The fear was constant and exhausting.

Meanwhile, back in New York City, people were dying at a furious pace, and healthcare providers were forced to wear trash bags and reuse masks to try and protect themselves against covid. I thought often about what my life would have looked like if I’d chosen to go to New York for my fellowship, and it still gives me nightmares. My heart aches for the healthcare providers who lived through those months, and even more for the ones who didn’t survive.

I graduated from fellowship (healthy) in August. In the midst of a massive pandemic-driven recession, I felt lucky to have been offered a job. But the logistics of getting out of Alaska were daunting. In the best of times, things like shipping services are limited. And covid has not been the best of times. I eventually figured out getting my stuff out of the state, and then faced the hurdle of getting myself to Minnesota.

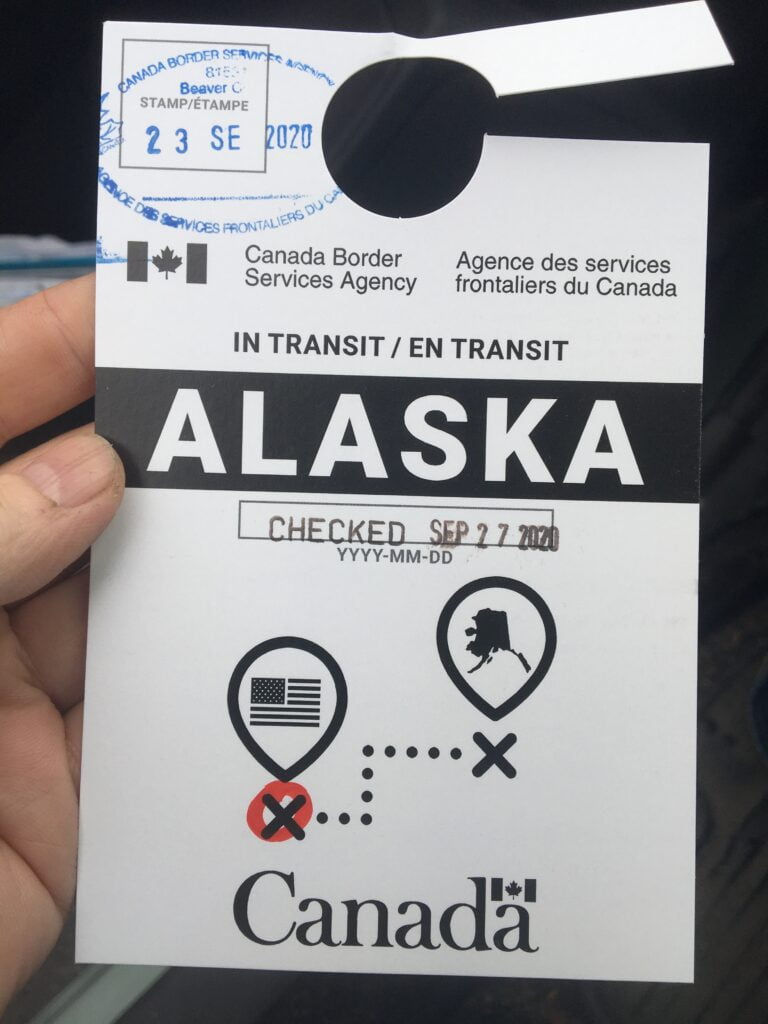

My drive through Canada deserves it’s own story. Suffice to say there’s nothing quite like driving seven hours to the border not knowing whether you’ll be let through (despite being an essential worker), then being handed some official papers and being told that if you don’t leave the country in five days in the Canadian government plans to issue a warrant for your arrest… It was a lot of driving, but I made it from Alaska to Seattle, and then from Seattle to Minnesota without incident.

I struggled to write this piece (ask James, it took me months!), because I want to be able to make meaning out of the last several months. I feel like most good travel narratives end with some pithy moral or the author talking about their great transformation (think “Wild” by Cheryl Strayd, or “A Walk in the Woods” by Bill Bryson). But it’s hard to come to any conclusions were still directly in the middle of it here.

I’m adjusting to my new home and my new job. I’m fortunate to have amazing friends, both locally and across the globe, who are checking in on me, and their love has made things easier. I’m still scared of getting sick, or my friends and family getting sick (so far at least 20 people I know have contracted covid, and a couple have died). I’m angry, most days, that people think covid is a hoax, or think that wearing a mask is “infringing on their freedoms” as if their refusal to wear one isn’t infringing on mine. At this point I’m trying to remember to keep putting one foot in front of the other. I’m trying to find joy where joy has to be found. I’m starting to feel a little hopeful that vaccines might arrive in time to protect me, though I hesitate to make any predictions about whether we’ll ever return to “normal life.” But I’m still dreaming of the day when I might be able to hit the road again. Stay safe out there. And wear a mask!